The opinion of TEFL, bilingualism and TLA and in Spain

Disclaimer: all quotations from Spanish resources are my own translations.

In this entry we are going to discuss the different beliefs parents, teachers, and students share about bilingual education around Spain. We are also going to discuss their opinions about English education and learning English as a second d or third language in Catalan schools and different Spain territories such as Murcia, Granada and Almería.

As always, I would like to start with Catalan education. As we have previously seen in anterior entries of this blog (as Multilingualism in the Catalan territory), Catalan schools offer three languages in their schools: Catalan, the main vehicular language, Spanish and English. Usually, English is labeled as their second language in schools, as the third languages tend to be French or German, which are offered during secondary and/or high school education, and Spanish is assumed to be another L1. This can be a bit misleading as in reality the L1 should be Catalan, as most classes are taught in Catalan; the L2 should be Spanish, as there are only a few subjects taught in Spanish; the L3 should be English, which is implemented around primary school; and then the L4, which would be these ‘foreign languages’ that high schools offer to students to expand their language repertoire.

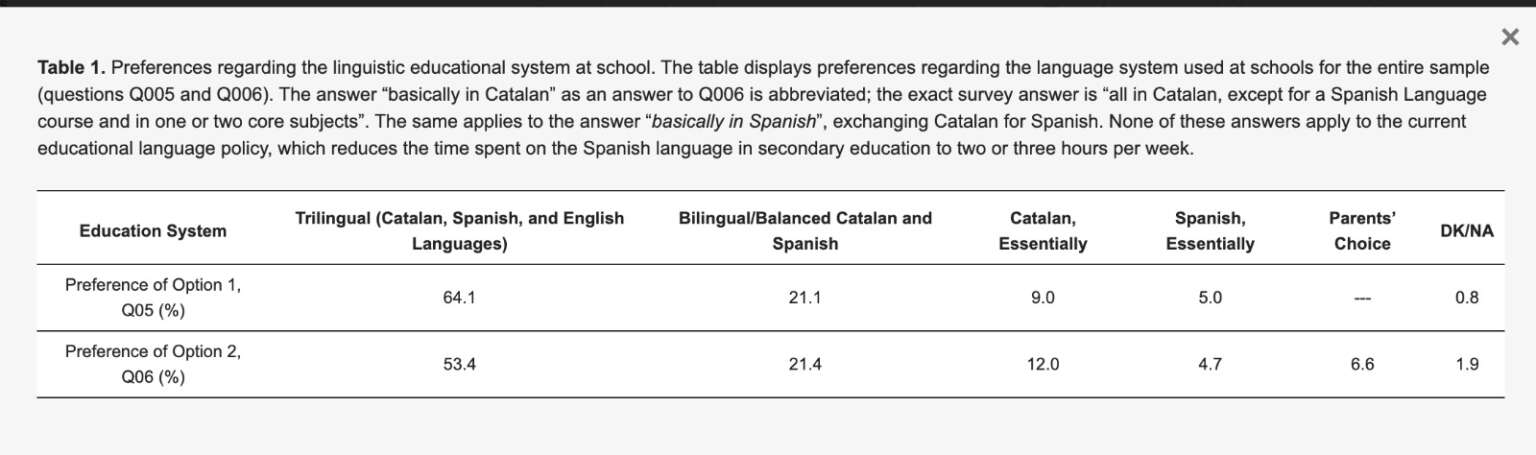

Therefore, when talking about Catalonia’s languages the focus is on Catalan, Spanish and English. I would like to take a look first at how the Catalan population views the linguistic immersion of schools in their territory. On August 2021, reporter Sergi Ill collected in his article El 85% de los catalanes rechaza la inmersión lingüística published in Economia Digital, the results of the study Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia done by the Josep Maria Oller, Albert Satorra and Adolf Tobeña (this investigation was done in English and you can find it attached down below in case you want to check out the full investigation). This investigation was done on citizens over eighteen years old, and they were asked about linguistic immersion in Catalan schools: whether they would prefer a trilingual, bilingual or monolingual education. As Sergi Ill (2021) rightfully collects from the study in his entry: “61, 4% of the interviewees prefer a trilingual (Catalan, Spanish and English) education where the three languages are equally taught, while the 21.1% prefer a bilingual education system (Catalan and Spanish) and only 14% would prefer a monolingual education (9% are in favor of all in Catalan classes while a 5% would prefer all in Spanish classes).” When asked about the educational system that the Generalitat de Catalunya should offer, 6.6% of the interviewees believe that it should be the parent's choice.

Table 1. Respondent's prefrences regarding the linguistic educational system at school. Retrieved from: Ill, S. (2021, August 30). El 85% de los catalanes rechaza la inmersión lingüística. Economía Digital. https://www.economiadigital.es/politica/educacion-cataluna-64-apuesta-misma-importancia-ingles-espanol-catalan.html

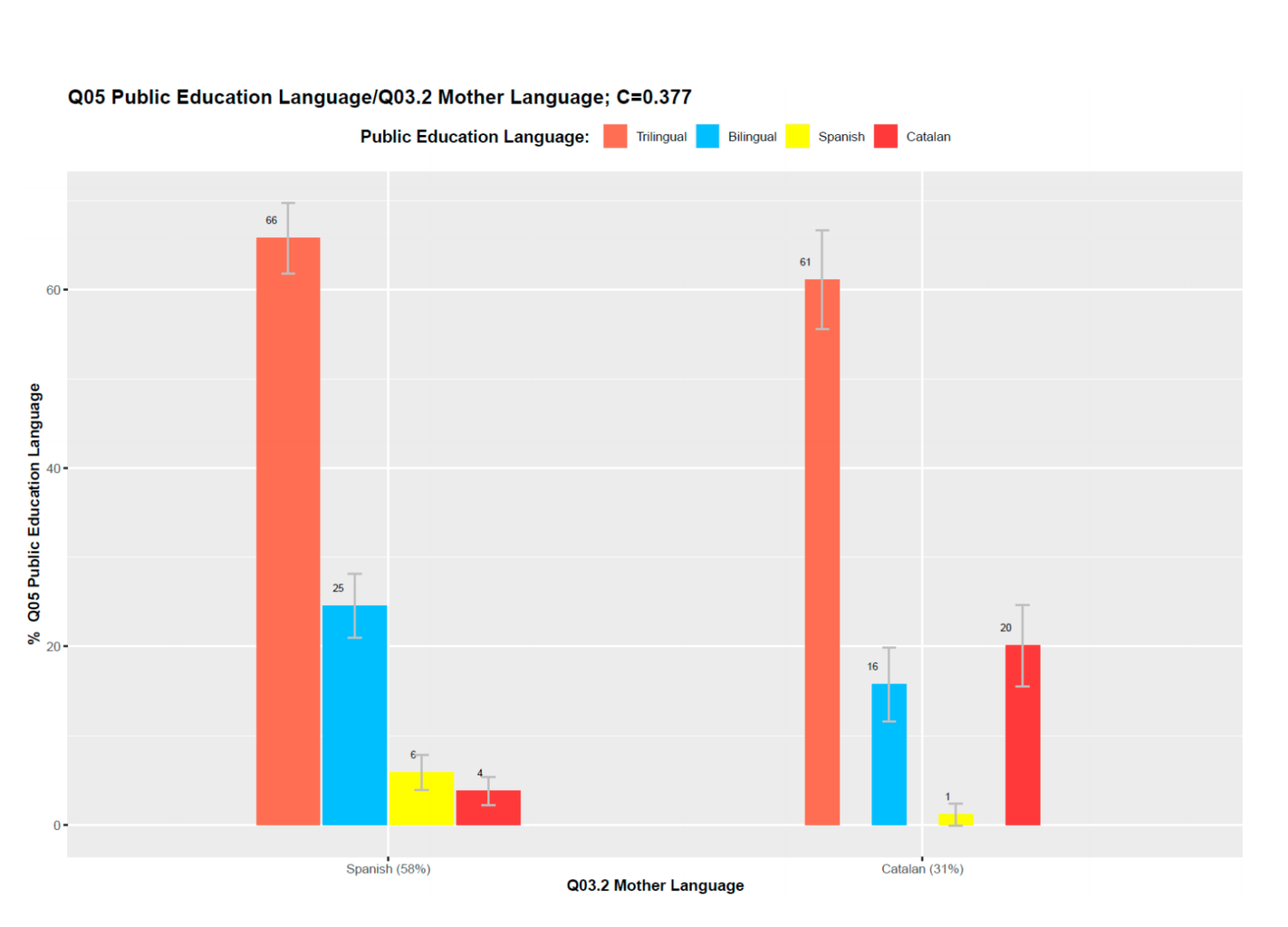

From this broad study of the linguistic system in Catalonia, we can conclude that many citizens are not too keen on the actual educational system. Regardless of whether they are native Spanish or Catalan speakers, both perspectives are more in favor of a trilingual linguistic project where the three languages are taught equally, something that is not being implemented at present in Catalonia.

Table 2. Educational model preferred by Catalans, according to their mother tongue. The data reflect similar results among both Catalan and Spanish speakers. Retrieved from: Ill, S. (2021, August 30). El 85% de los catalanes rechaza la inmersión lingüística. Economía Digital. https://www.economiadigital.es/politica/educacion-cataluna-64-apuesta-misma-importancia-ingles-espanol-catalan.html

There are many resources published around 2010 and 2015 all over the internet about how Spaniards are bad at English or questioning why they spoke it ‘badly’ (e.g. Por qué a los españoles se nos da mal el inglés² by Fernando Galvan or ¿Por qué hablamos los españoles tan mal el inglés?³ by Gema Lendoiro that talk about the main factors about learning the language: how bilinguals have more advantages, how speaking many languages since being a kid does not affect negatively and how one of the main issues is our own linguistic and phonetics characteristics. Likewise, some other online newspaper articles such as Los profesores necesitarían al menos un nivel más de inglés que sus alumnos by Adrian Arcos (2020) and many others argue that English teachers in Spain should have higher levels of English and that the mandatory level nowadays is lower than it should be (all this information collected based on professional’s opinions and solidly based studies). Likewise, as Carles Ribes introduces in his entry El model trilingüe s’estanca a l’escola catalana per dèficit d’anglès published in the Spanish newspaper El País, Manel Pulido (general secretary of the Federation of Education of CCOO in Catalonia): “There is a need for more resources, we demand double the number of teachers, and the three hours of English per week should be divided into two groups of 15 students” (Busquets, 2019). In addition, Mark Lapinski (head of the association of English teachers in Barcelona TEFL Teachers Educations (BTTA)) states: “I have the impression that the level of many teachers [in the Catalan school] is not as high as it should be, I have seen in the notes of my student's errors of their teachers.” (Busquets, 2019). Therefore, we can see that some teachers and professionals are not too satisfied when talking about how to learn, in this case, English in class.

Further elaborating on the opinion of the teaching staff, I would like to take a look at the study A Study on CLIL Secondary School Teachers in Spain: Views, Concerns and Needs conducted by Inmaculada Senra-Silva on 2021, as “the results reveal that, in general, the difficulties faced by teachers in implementing a bilingual program are numerous, and many informants believe that the English bilingual program is in need of comprehensive reform”. (2021, p. 1). While interviewing, many anonymous teachers from all over Spain were asked to self-assess themselves. They talked about their levels of English and their teaching experience (focusing on CLIL especially), but what I am most interested in is that: “A good number of respondents point to their poor command of and fluency in the English language. Others complain about their lack of linguistic resources. That leads many to pay more attention to their linguistic skills than to the contents they teach. In this sense, they believed they waste a lot of time that could be employed on designing and improving the contents to be taught.” (2021, p.5). When asked about the bilingual programs they teach in, teachers mostly believe that for starters, there should be a change of mentality and work dynamics, more time for meetings and to be able to organize things in the right way, and finally, that there should be less teaching hours and more to prepare the materials (Senra-Silva, 2021, p.7). Likewise, in this interview, teachers especially complain about the low hours of preparation they are given and the need for more CLIL material as it takes a lot of hours to prepare them, and they do not have enough time. (Senra-Silva, 2021, p.9).

This idea of lacking material and low hours of preparation is not new to teachers’ opinions. Many online sources and investigations can show that most teachers are not fully satisfied with the tools and material they are given to prepare or conduct their classes. Therefore, we can see that teachers do not seem to be happy with the teaching system they work with.

Focusing on student’s beliefs and experiences, a study conducted by Xavier Marin Rubio and Irati Diert Boté (2018) named Learning English in Catalonia: beliefs and emotions through small stories and iterativity, interviews students about their relationship with English and learning it as a third-language. In this investigation, students, apart from talking about why they learned English and their emotions in class or related to the language, also gave their opinions about the teaching methodology they received. A student named Daniel argued that the English levels taught in schools are bad and that they are unable to learn. Another student named Yolanda claimed that the issue is not the teacher’s English level, but rather how they teach the language (2018, p.15). A different student named Claudia, who had no problem with the teacher's level, argued that the lessons are low and poor, but that the teachers have a curriculum to follow (2018, p. 19). Likewise, students agree when it comes to the way grammar is taught: “the teacher is presented as mainly carrying out grammar explanations and activities and very little speaking tasks, while the students portray themselves as being unable to learn or improve their English because of the excess of grammar in the class, repetitive and uncommunicative activities, and little practice of the language. Moreover, and probably as a consequence, they relate exclusively negative emotions to the English learning setting; apart from demotivation, boredom, irritation and frustration, identified by Yolanda, participants also mention feelings of insecurity, fear and embarrassment.” (Marin Rubio and Diert Boté, 2018, p.22). This investigation concludes with the results that some students believe that the issue is with the curriculum, while others believe it is because of the teacher’s (teaching) methodology.

Now let’s take a brief look at some other regions of the country and not only Catalonia. The main difference would be that some of these regions are not “bilingual” like Catalonia (where they have two languages, only different dialects) and therefore when talking about English they refer to it as their second language. Let’s start with Murcia. There is a study done by Mª Ángeles Hernández Prados, Mª José Gambín Martínez and Ana Carmen Tolino Fernández-Henarejos named The perception of families about the teaching of second languages (2017), where after some studies and surveys were conducted, most of the parents whose children are part of a bilingual program are satisfied with the level of English and show a favorable attitude over these programs. In this study, the parents also comment on the myths of bilingualism and by the end of the survey, we can see that they are delighted with bilingualism and their academic performance which puts an end to parental concerns, the result of precedents research, the possibility of delays and disorders in the linguistic acquisition of their children, as well as the fact that bilingualism could end up causing them certain confusions and end up mixing them up with other languages. (Hernández Prados, M. A; Gambín Martínez, Mº. J; Tolino Fernández-Henarejos, A. C. 2017, p. 13).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics on families' satisfaction with foreign language learning. Retrieved from: Mª Ángeles Hernández Prados, MA; Gambín Martínez, M. J; Tolino Fernández-Henarejos, AC. (2017). La percepción de las familias ante la enseñanza de segundas lenguas. The perception of families about the teaching of second languages. Revista Fuentes I.S.S.N.: 1575-7072 e-I.S.S.N.: 2172-77752018, 20(1), 11-27 http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/revistafuentes.2018.v20.i1.01, page 9.

In addition, a study made on 3rd and 4th-grade ESO students (14 to 17 years old) in Granada, Almería, and Murcia, named Las actitudes del alumnado hacia el aprendizaje del inglés como idioma extranjero: estudio de una muestra en el sur de España (2008) and done by Diego Uribe, José Gutiérrez and Daniel Madrid, showed that the students interviewed did not really find necessary to earn a foreign language (opposite to what parents believe). The attitudes they showed were not indifferent or positive, even though there is a “slight inclination towards a positive attitude rather than a negative one”. (2007. p. 8).

Before concluding this brief investigation, it is important to state that there are many sources (such as The perception of families about the teaching of second languages (2017), El 100% de los padres piensa que aprender inglés es muy importante (2013) and El 94% de los padres considera el inglés la asignatura más importante para el futuro de sus hijos (2014)) all over the web, where you can read about the parent's concerns and reasons for their kids to learn more languages (but especially English as it is the ‘international language’): job opportunities, good universities, and other educational reasons. So parents still believe that learning languages are very important, however, they are less worried that bilingualism or plurilingualism might negatively affect children and are more supportive of having a multilingual education.

In conclusion, we can see that neither teachers nor parents nor students are fully satisfied with the way English is learned and taught in schools. While opinions might differ, many agree on how there is an issue in the educational system, especially when learning languages or English in specific, and that there should be a change. Likewise, many believe that the level is too low and that a change is also needed in this area.

¹OllerJM, Satorra A, Tobeña A. Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia. Genealogy. 2021; 5(3):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030077

²Galván, F. (201, July 17th). Por qué a los españoles se nos da mal el inglés. El País. Retrieved from: http://juancarlosgarcialorenzo.eu/downloads/bachillerato/2/Porqu%C3%A9alosespa%C3%B1olessenosdamalelingl%C3%A9s.pdf

³Lendoiro, G. (2014, April 4). ¿Por qué hablamos los españoles tan mal el inglés? Abc. https://www.abc.es/familia-educacion/20140404/abci-hablar-varios-idiomas-201404041054.html

References used on this entry:

Busquets, J. P. (2019, December 26). El model trilingüe s’estanca a l’escola catalana per dèficit d’anglès. El País. https://elpais.com/cat/2019/12/26/catalunya/1577380816_183510.html

Diert-Boté, I, Martin-rubio, X. (2018). Learning English in Catalonia: Beliefs and emotions through small stories and iterativity. Narrative Inquiry. 28. 56-74. 10.1075/ni.17029.die. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325217698_Learning_English_in_Catalonia_Beliefs_and_emotions_through_small_stories_and_iterativity/citations

Galván, F. (201, July 17th). Por qué a los españoles se nos da mal el inglés. El País. http://juancarlosgarcialorenzo.eu/downloads/bachillerato/2/Porqu%C3%A9alosespa%C3%B1olessenosdamalelingl%C3%A9s.pdf

Ill, S. (2021, August 30). El 85% de los catalanes rechaza la inmersión lingüística. Economía Digital. https://www.economiadigital.es/politica/educacion-cataluna-64-apuesta-misma-importancia-ingles-espanol-catalan.html

Lendoiro, G. (2014, April 4). ¿Por qué hablamos los españoles tan mal el inglés? Abc. https://www.abc.es/familia-educacion/20140404/abci-hablar-varios-idiomas-201404041054.html

Mª Ángeles Hernández Prados, MA; Gambín Martínez, M. J; Tolino Fernández-Henarejos, AC. (2017). La percepción de las familias ante la enseñanza de segundas lenguas. The perception of families about the teaching of second languages. Revista Fuentes I.S.S.N.: 1575-7072 e-I.S.S.N.: 2172-77752018, 20(1), 11-27 http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/revistafuentes.2018.v20.i1.01

Oller JM, Satorra A, Tobeña A. Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia. Genealogy. 2021; 5(3):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030077

Pascual, S. (2013, December 17). El 100% de los padres piensa que aprender inglés es muy importante. formaZion.com. https://www.formazion.com/noticias_formacion/el-100-de-los-padres-piensa-que-aprender-ingles-es-muy-importante-org-2627.html

Senra-Silva, I. (2021). A study on CLIL secondary school teachers in Spain: Views, concerns and needs, in Complutense Journal of English Studies 29, 49-68. file:///C:/Users/34677/Downloads/maitgarc,+049-068%20(1).pdf

Uribe, D.; Gutiérrez, J.; Madrid, D. Las actitudes del alumnado hacia el aprendizaje del inglés como idioma extranjero: estudio de una muestra en el sur de España. Porta Linguarum, 10: 85-100 (2008). Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/31782

Comments

Post a Comment